A. Shipwright

Imagine an RPG meant to be played with the traditional setup of players and GM but with the following rule:

“When a PC takes any action that is uncertain and risky but possible, flip a coin. If heads, they succeed. If tails, they fail. “

Whaddya think?

Understandable? Yep. Functional? Yep. Arbitrary? Absolutely.

Imagine: jumping a pit, fighting a monster, convincing a guard to let you pass all grant you exactly 50% chance of success. It feels wrong.

As a player, it becomes your main aim to convince the GM that what you are doing is not uncertain or risky, granting automatic success or that your impossible action actually is possible and deserves a 50/50 shot of working. It looks as sterile as this:

And this is how I thought of the games Into the Odd and Electric Bastionland. Here’s what I mean: a character with all average stats has the same chance of doing anything. In both of these games, you have 3d6 in each of the three stats (I’ve written about how glorious these stats are and how they’ve had a profound impact and me and you should read it. Ahem.). You’re looking to roll equal to or under these stats with a d20. So if you rolled all 10s or 11s, which is completely average, you would have a 50 or 55% chance of succeeding. For everything.

Why is this a problem?

- Your fictional positioning does not matter. That’s just “fancy speak” for what’s going on in the game. If you always have 50% chance of succeeding, then what happens in the game isn’t affecting the mechanics, in this case the die roll. If having or not having a grappling hook isn’t enough to change my odds of climbing a wall, then my attempt to make things easier are in vain. It leaves a bad feeling in the mouth to not at least be recognized for additional effort in shoring up your chances.

- Your approach doesn’t matter either then. If it’s not enough to secure auto-success or auto-fail, forget it. Intimidating, bargaining with, and charming the princess are all the same, so long as the situation is still defined as risky but possible. Who cares?

- All characters are mechanically the same then too. You have 50% chance, I have 50% chance. ItO and EB “sidestep” this by making stats random, but there is still a tendency towards “average” because of the bell-curve on a 3d6. Having 10 instead of 11 in DEX doesn’t change how someone plays the game.

Now other games have ways of maneuvering those odds so that you as a player have a better or worse chance at succeeding. Most games call it “advantage”, and that’s what we’ll call it here (there is also the flip side of disadvantage, but let’s just talk advantage to keep it simple). ItO and EB don’t have advantage. Like, at all. Yet games based on Into the Odd, like Mausritter have since added advantage to the game. What gives? Is the designer just oblivious to modern and popular design? I mean, the advantage mechanic was the highest-praised innovation in 5e Dungeons and Dragons. Most games designed nowadays include some form of advantage.

We’ll get back to that. First, let’s look at the role of advantage in other games and what makes it important. Mausritter, Maze Rats, Knave, and Red Ink Adventures are all relatives of Into the Odd and all have advantage written in their rules. In each of them, a character with advantage rolls more dice and takes the highest which increases their chance of success. However, what makes these games different is that all of them start players off at a statistical disadvantage:

- Mausritter uses the same “d20, roll-under” system as Into the Odd, but 64.35% of stats rolled by characters in Mausritter are below 10, which means a majority of PC stats have less than a 50% chance of success.

- In Knave, you roll a d20 and add a stat with success being above a 15. With the average starting stat being 2, you have only a 35% chance of success.

- Red Ink Adventures has you rolling 1d6 and adding a stat, looking for 6 or higher. The average stat is 1, so you’re looking at a 33% chance of success.

- In Maze Rats, you roll 2d6 and add a stat with a success being 10 or higher. The average starting is stat +1, meaning you have a 27.7% chance of success.

As a player in any of these games you don’t want to roll. Ever. The odds are against you, but you also cannot avoid doing risky things as an adventurer. So roll you must. This is where advantage comes in. You can advocate for your situation BEFORE making the roll. “I’m using my grappling hook. Does that give me advantage?” “Does Steve pulling the rope up help me climb the wall?” “What if use the mossiest part of the wall to stick to as I climb? Does that help?” Players are thinking strategically then, looking for an edge to serve their situation. Any bit of information is possible leverage. “I mention the princess’s lost ring. Could I use the promise of finding it for her as an advantage?” Players are thinking about what’s going on more than if they were just nihilistically flipping a coin.

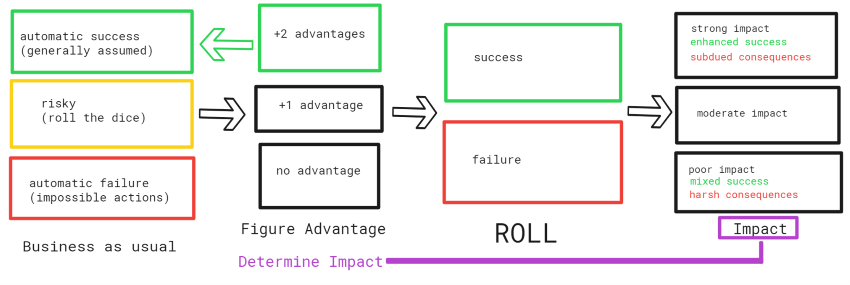

As a bonus, Maze Rats (and Red Ink Adventures) use this rule: “if two or more advantages apply, the action is no longer risky and no roll is required.” It just jumps up to automatic success. Graphically, it looks something like this:

Why do these games do this? It hammers home an old-school princple of the game: you have to work for it. You have to work for everything and nothing comes easy. The default for risky actions is failure. You better plan your advantages as best you can, because its gonna be tough.

This looks way more sophisticated than the “coin flipping RPG” I mentioned at the beginning. It even builds the philosophy of the game. It’s easy to run a game of high lethality and difficulty when it’s baked into the mechanics. It makes players work to get an edge before they roll the dice.

But what if there was a way to make the “coin-flipping RPG” more sophisticated and fix my “issue” with Into the Odd and Electric Bastionland? There is. Chris McDowall wrote an article about advantage in ItO and EB and it changed my mind. Instead of summarizing it, I’ll just apply it here and to demonstrate its usefulness.

When taking a risky action, determine the potential impact of that action before rolling any dice or flipping any coins.

With a strong impact or advantageous position, the action has enhanced success on a success and/or subdued consequences on a failure.

With a poor impact or disadvantageous position, the action has mixed success on a success and/or harsh consequences on a failure.

Here’s what it looks like:

The answer to the question “why don’t Into the Odd and Electric Bastionland have advantage?” is that they do. It just doesn’t look like advantage as we think of it. It doesn’t change the die roll at all.

Instead of altering the literal percentage chance of success and failure, “advantage” alters the impact of success and failure.

This is how to make the “coin flipping RPG” work, by the way. Let’s look back at those three points I outlined:

- Your fictional positioning does not matter. Your position instead changes the impact. Using a grappling hook to climb the wall instead of just my bare hands may give enhanced success by allowing me to climb faster or more safely.

- Your approach doesn’t matter either then. The approaches changes the impact of success and/or failure. Note that it doesn’t have to be both. Failing to negotiate with the princess may only result in her getting annoyed at you. Threaten to kill her brother and fail the roll? She calls the guards on you. Enjoy being locked away.

- All characters are mechanically the same. Sure, you have the same chances of success/failure, but the thief screwing up a stealth roll may result in a classic “Is anyone there?” from a nearby guard, whereas a full plate paladin would trip and crash down the stairs, alerting the entire keep.

The upside to this is that it’s the fiction of the game that is affected by this, which is a huge plus for a role-playing game. But, it doesn’t look as snazzy. Rolling more dice is a tactile, observable difference at the table.

What’s the result of all this jabbering and these poorly drawn graphs? Even with the most simple system, you can make game work well with an effective framework. For taking risky actions, it means changing the impact of that action based on the character’s advantages and disadvantages.

That, and you could mix the two approaches of mechanical, dice-driven advantage AND fiction-driven impact:

That’s all for now. I’ll write some shorter posts that are coming up. I’ve just been hunkering down in my bunker, so longer posts are inevitable. Stay healthy!

EDIT (July 6th, 2021): I received many comments after writing this about how John Harper (great designers) came to a similar conclusion in the days of G+. Here is the document he produced to demonstrate some of these ideas further.

This is probably the most clear and comprehensible post on fictional positioning and impact.

Also thanks for the graphial representations. They’re very useful to have!