This is an unpaid review. Chris Engle sent me a digital copy of his new book, Social Matrix Games and asked if I would be interested in reviewing. I know these kinds of games are an interest in my readers and myself, so I was happy to oblige.

Matrix games by Chris Engle can be summed up as freeform games about problem solving.

We’ve talked about Open Strategy Games before which are sort of a PvP flavor of matrix/military games, but Matrix Games are the broader category. And this book showed me how that is the case.

The rules are simple, the applications near-infinite:

Matrix Game Rules: Start with a problem. Say what happens next. There is no order of play. Anyone can add to or alter what happens. All players may ask a player to roll if they don’t like what they said. Roll 2d6. ≥7: The action happens and cannot be altered. ≤6: It does not happen and cannot happen in the game. The game ends when the problem is solved.

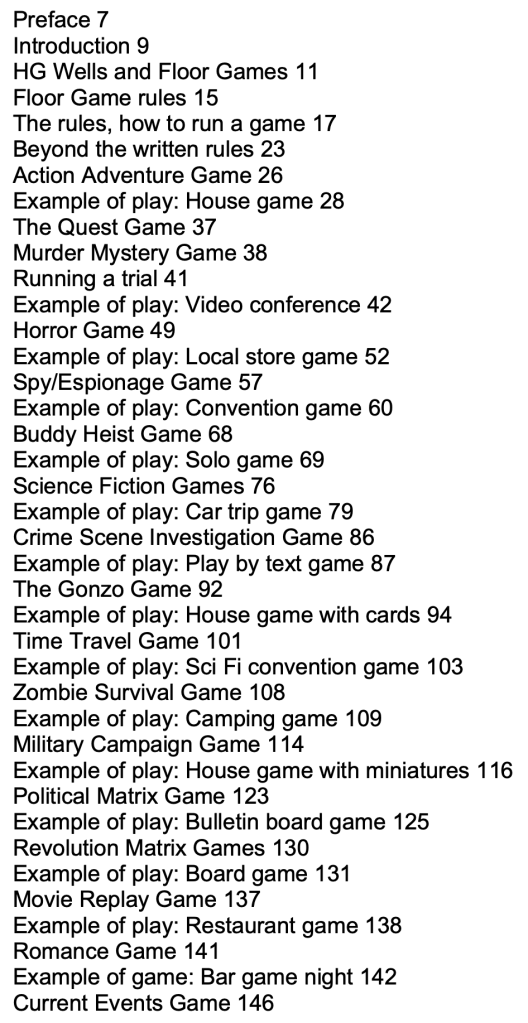

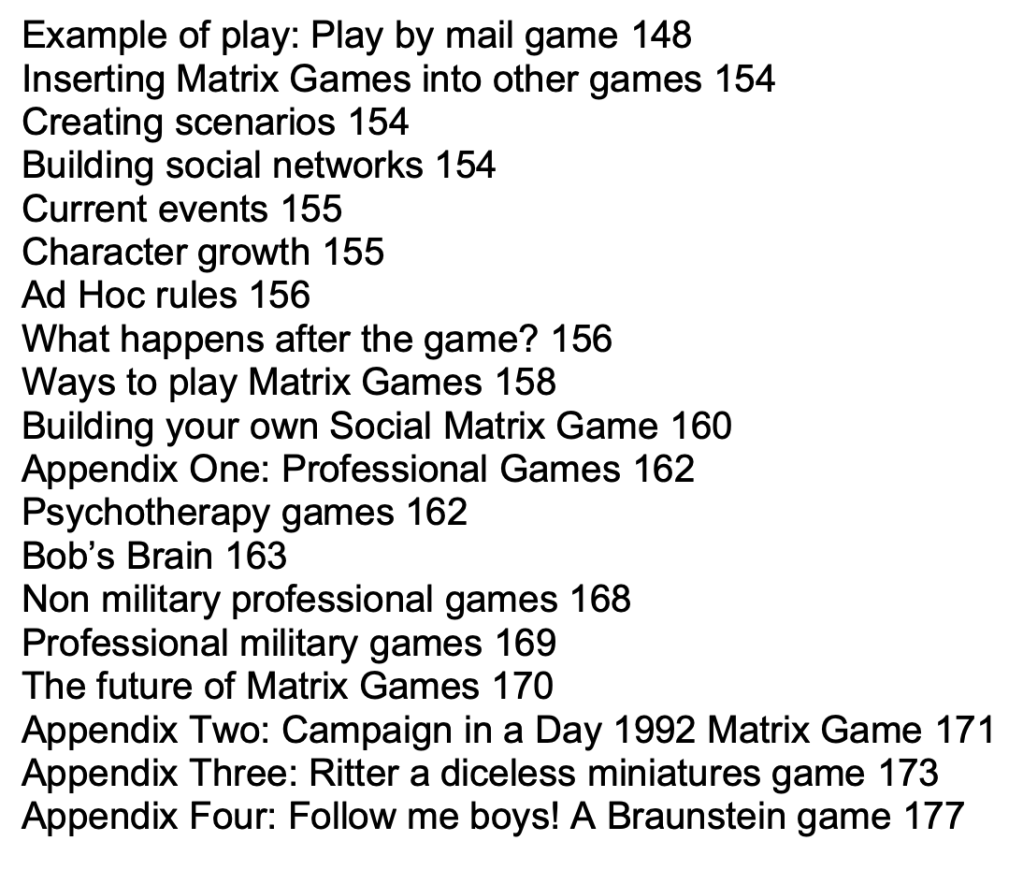

If that simplicity is overwhelming, that’s totally understandable. In this book, Chris gives 20 examples in specific scenarios about how to apply this framework to make for interesting freeform sessions of play. The genres include action-adventure, murder mysteries, military campaigns, romance, horror, and more. The modalities/mediums include playing around a table, over video conference, solo, on a car trip, at a convention, at a restaurant, and more. THIS is the all-terrain game, favoring words over numbers and minimal dice rolls.

To give you a flavor of what’s all in here, here’s the table of contents:

The book opens with a heartwarming anecdote from HG Wells about his rambunctious boys during a rainstorm. His wife demanded that he settle the boys down who were going crazy indoors. He sat down at a collection of toys and began arranging them in preparation for a sort of safari adventure the characters were about to go on. The boys jumped in and began playing immediately. One child went in one direction and the other went another. Some disagreements came up about how best to proceed, and Wells resolved the impasse by flipping a coin. The boys continued adding detail to the adventure. They would describe obstacles and successes to keep the story interesting. Wells would also add ways to up the steaks.

Wells later wrote this up. Just look at this gold:

Father will lay out the toys and say what the game is about.

Wells, “The Floor Game”

The boys play by taking turns adding to the story. Listen and don’t talk over one another no matter how excited or angry you get.

Work together to tell an exciting story.

One boy picks up a toy and says what happens. Move the toys around as you speak and make appropriate noises as you go. Animal cries, machine sounds, and conversations between toy people are all okay.

After adding to the story let your brother have a turn.

Your brother may add to or even change your story. If any boy doesn’t like a change they may ask father to flip the Queen Victoria Penny to see who wins.

Don’t get cross or knock the game over if your favorite toy gets killed. Say how they are saved.

Father can add problems to the game. He may also say no to any addition if it is unfair and will make the boys fight.

The boys may shoot marbles at toys whenever they like. If they fall over they are dead.

The game ends when Father says so or when Mother calls us for dinner.

And so the afternoon passed, and the boys were excited about this “floor game”. Engle takes the same spirit and applies to these different genres and modes of play.

Something very charming about the book Chris wrote is that there are so many examples with varying outcomes. He describes players playing and chatting, and then pausing for a quick snack or restroom break and then starting back up again. He describes a students valiant attempt to begin a matrix game using a bulletin board and failing miserably. He also describes a horror game where a player goes to far and the game ends abruptly, folks abandoning the disruptive player. Through all these examples of play and example scenarios, Chris is able to illustrate the depth and variety of play in matrix games.

The whole book is inspiring when it comes to the low barrier to entry of starting and creating games of your own. It emphasizes several times at all you need are players, 2d6, some scratch paper, and a place to play. You’re also encouraged to bring your own tactile elements, like miniatures, maps, or stolen elements from other card games or board games. It’s wonderful.

In creating a scenario of your own, come up with a central problem. List a number of characters that are interested in that problem. List a number of locations where the problem could be encountered or addressed. Players “champion” a character. The host goes around and asks what each character is up to before the problem. Then the host asks “what happens next?”

Note the frame of the question, it’s essential: This is NOT “what do you do?” You’re not playing a role, you are an author, a contributor. “What happens next?” means you are adding details, problems, and solutions while also giving others a chance to add to what’s going on. And then everyone is surprised by the outcome and how it happens. Some folks who regularly play RPGs may not like having to invent detail, that’s okay. A lot of the setting and character assumptions (if smartly-written) do a lot of the legwork, you are just tasked with saying what happens next.

There’s also a specific end-state to the game, something ALL RPGs could use more of: the game ends when the problem is solved. Resolution brings about a clear ending. It’s why every board game rules explanation I’ve ever given starts with how the game ends and how do we determine who wins. It’s the right frame for 99% of board games and here is no different.

Application

Just to show you how easy this is to get going, let me show you. And because it’s me, I adjusted the rules a smidge.

Rules: Start with a problem. Say what happens next. There is no order of play. Anyone can add to what happens. Any player may challenge what another player says and tell them to roll 2d6. On a 7+, what was said happens and cannot be altered. On a 6-, it does not happen and cannot happen. The host may veto what another player says, but this must be done before dice are rolled. The game ends when the problem is resolved.

Romance in Agrabah

The Princess of Agrabah is of marrying age. The palace doors are open and all suitors are welcome. Many men will try their hands at winning hers. Who will the princess marry?

Characters:

- Tale Teller, from a faraway place

- Horse Rider, champion athlete and student

- Idiot Savant, wandering wildcard

- Accomplished Mercenary, back from the warfront.

- Handsome Caregiver, rugged nobody

- Disreputable Courtier, rival to the mercenary

- Princess, wants to choose for herself.

- The Sultan, wants the most politically advantageous outcome.

- Young Prince, brother to the princess.

- Loyal Attendant, wants what’s best for the princess.

Locations:

- Agrabah Palace

- Agrabah Market

- Agrabah Slums

- Open Desert

- Oasis

- Lost Cave

And that’s it. You might use the “just one more detail” method to add names or a more complex relationship map, or a map of the physical space or bring parchment for people to write love letters. Drama abounds!

All in all, any product that gets me create and imagine something and then blog about it is a worthy thing. I read the whole thing in two sittings and couldn’t stop writing down ideas for games and interesting rules that would enhance the matrix game flavor. All in all, a great read.

I encourage you to check out Chris’s works here on Lulu for further reading on matrix games.

Is it possible to buy pdf from Chris Engle?

Asked Chris, he said he’d get something up soon. I’ll reply here and update the post when I get a link.

https://www.drivethrurpg.com/product/460191/Social-Matrix-Games